An electrical panel is the control center for a home’s power distribution. It’s the point where the utility service hands power off to the rest of the house. Every circuit, breaker, and appliance load routes through it. When the panel is outdated, undersized, or physically compromised, the electrical system can no longer operate within the tolerances modern homes require. That’s when breakers trip under routine use, voltage sags show up when larger equipment starts, and adding new circuits becomes difficult without workarounds that introduce risk.

Most of the time, the panel itself isn’t “broken” in the obvious sense. It’s just no longer matched to how the house is being used. Homes today carry sustained electrical loads that weren’t common when many panels were originally installed. Larger HVAC equipment, higher-demand kitchen appliances, electric vehicle charging, and modern electronics all pull power in ways older panels weren’t designed to support continuously.

When the panel can’t comfortably carry that load, it starts showing stress through heat, wear at breaker connections, and a lack of available capacity. Electrical panel upgrades and replacements exist to correct that mismatch.

Sometimes the issue is capacity, where the home needs more amperage and space to safely distribute power. Other times the problem is the panel’s condition or design, where the enclosure, bus bars, or breaker system no longer meet modern safety expectations. In both cases, the underlying issue is the same: the electrical demand of the home has moved forward, and the panel hasn’t kept up. Addressing that gap restores headroom, stability, and a margin of safety the system depends on to function the way it should.

What an Electrical Panel Does in a Modern Home

An electrical panel receives power from the utility service and divides it into individual branch circuits. It provides overcurrent protection through breakers, establishes grounding and bonding, and defines how much electrical load the home can safely carry at one time.

The service rating, bus design, and breaker configuration determine how loads are balanced and how much capacity remains available for expansion. When those limits are respected, the system operates predictably. When they’re pushed too far, problems start showing up in ways that feel random but usually trace back to load management at the panel.

Again, modern homes place sustained, simultaneous demands on electrical systems that were uncommon even a few decades ago. High-efficiency HVAC systems cycle differently and often draw higher starting currents. Induction ranges and electric ovens pull significant amperage for extended periods. Electric vehicle chargers introduce long-duration loads that can run for hours at a time. Heat pumps, tankless water heaters, and advanced electronics all require dedicated circuits and stable voltage to operate properly.

Panels installed years ago were typically designed around lighter, intermittent loads and fewer large appliances running at the same time. They often lack the breaker space, bus capacity, or service amperage needed to support today’s electrical patterns without running near their limits. As homes evolve, the panel becomes the deciding factor in whether those systems can operate reliably or whether the electrical infrastructure needs to be brought up to modern expectations.

Panel Upgrade vs. Replacement

Electrical Panel Upgrade

A panel upgrade is about capacity and headroom. The goal is to increase how much power the home can safely distribute and how flexibly that power can be managed. This usually involves raising the service amperage, installing a larger panel enclosure with more breaker space, and reworking circuit layouts to meet current electrical code. In practical terms, that often means moving from a 60-amp or 100-amp service to 150 or 200 amps, along with modern breakers designed to handle sustained loads more reliably.

Upgrades are most often driven by change and expansion. A new HVAC system, an electric range replacing gas, a shop addition, or an EV charger can all push an older panel past its comfort zone. Even when everything technically works, the panel may be operating with little margin. Breakers run warmer, load calculations get tight, and adding circuits becomes a balancing act instead of a straightforward installation. A panel upgrade restores that margin, giving the system room to operate without riding its limits.

Electrical Panel Replacement

Panel replacement is usually driven by the condition of the equipment itself rather than a specific need for more power. In these cases, the service amperage may stay the same, but the panel is replaced because its design or physical state no longer meets safety expectations. Over time, heat cycling, moisture, and mechanical wear take a toll on bus bars, breaker connections, and enclosure components.

Replacement is common when there are signs of overheating, corrosion, loose or damaged connections, or breakers that no longer seat properly. It’s also necessary when a panel model has known defects or is no longer supported by the manufacturer. Some older panels cannot safely accept modern breakers, and substitutes introduce compatibility risks that aren’t acceptable in a critical system. Replacing the panel removes those variables and brings the electrical system back to a known, reliable baseline without changing the overall capacity of the service.

Signs an Electrical Panel Is No Longer Adequate

Panels rarely fail without warning. The symptoms tend to surface gradually and become more frequent over time. By the time the issue feels urgent, the panel may have been operating outside its comfort zone for a while.

One of the earliest indicators is breakers tripping during routine use. This isn’t about a space heater plugged into the wrong outlet or a one-off overload. It’s breakers opening when normal appliances run together, or when equipment that used to operate without issue suddenly causes interruptions.

Flickering or dimming lights when large equipment starts indicate voltage drop under load. That drop may be caused by limited panel capacity, aging panel components, or resistance elsewhere in the electrical system, and it often warrants a closer look at the panel as part of a broader evaluation.

Breaker handles that feel warm, show discoloration, or have a faint burned smell indicate resistance where there shouldn’t be any. Buzzing or crackling from the panel enclosure is another red flag. Noise can mean arcing, loose connections, or stressed components inside the enclosure, all of which need immediate attention.

Panels that are full or nearly full often rely on shared circuits or creative breaker arrangements to keep things running. When there’s no room left to add a circuit without doubling up or cutting corners, the panel has reached the end of its useful capacity, even if the amperage rating looks acceptable on paper.

Rust inside the enclosure, signs of moisture intrusion, cracked insulation on incoming or branch wiring, or brittle conductors at breaker terminations all point to long-term physical deterioration. Electrical equipment depends on tight, clean connections. Once corrosion or material breakdown enters the picture, reliability drops and risk increases.

Taken together, these signs indicate a panel that’s no longer matched to the demands placed on it. Addressing them early keeps the electrical system predictable and avoids the kind of cascading problems that start small and end with larger repairs than anyone planned for.

Overloaded Panels and Circuit Limitations

Older panels often rely on shared circuits or double-tapped breakers to compensate for limited space. This approach may have been acceptable under older codes, but it creates reliability and safety issues under modern usage patterns.

Overloaded panels operate closer to their thermal limits. That increases wear on breakers, raises internal temperatures, and shortens component lifespan. Upgrading the panel restores headroom so circuits operate within intended parameters.

Generators, Backup Power, and Transfer Switches

Adding backup power changes how electricity enters and leaves the home. Whether the system uses a portable generator with a manual transfer switch or has a permanent home standby generator installation with an automatic transfer switch (ATS), the electrical panel becomes the control point where normal utility power and alternate power are managed. That makes the panel’s condition, layout, and compatibility directly relevant.

Most transfer switch installations require either dedicated breaker space in the panel or a listed interlock that prevents utility power and generator power from feeding the system at the same time. Older panels are often full, not designed to accept interlocks, or no longer listed for generator backfeed connections. In those cases, the limitation isn’t the generator itself. It’s the panel’s ability to support a safe, code-compliant connection.

Backup power also forces clearer decisions about load management. A manual transfer switch typically feeds a subset of essential circuits, which must be identified, labeled, and separated at the panel. Automatic transfer switch systems go further, often relying on priority circuits or load-shedding logic to keep generator demand within safe limits. Panels that are crowded, poorly organized, or already operating near capacity make this process more complicated and less reliable.

Code requirements play a role as well. Generator installations trigger inspections that closely examine grounding, bonding, neutral handling, and service disconnect configuration. Panels installed under older standards may not meet current requirements for alternate power sources without modification or replacement, even if they have been operating without issue on utility power alone.

For these reasons, backup power projects often uncover panel limitations that weren’t obvious before. Evaluating the panel early in the planning process helps determine whether the existing equipment can support a transfer switch safely or whether panel upgrades or replacement are needed to integrate backup power properly.

Appliance-Driven Reasons for a Panel Upgrade

Many panel upgrades are triggered by a single new appliance. Electric vehicle chargers are a common example. Level 2 chargers can charge much faster, but they draw a sustained load that older panels cannot support without exceeding safe operating limits.

Other appliances that frequently force panel upgrades include electric ranges replacing gas, heat pump systems, electric dryers, hot tubs, and whole-home backup power equipment. Even if each appliance works independently, the combined load can exceed the panel’s rated capacity.

Load calculations determine whether the existing panel can safely handle the addition. When the margin is too tight, an upgrade becomes a requirement rather than an option.

Here’s a quick list of some of the most common upgrade-triggering additions:

- Electric vehicle Level 2 chargers

- Electric ranges or wall ovens replacing gas

- Heat pump HVAC systems

- Electric dryers replacing gas models

- Tankless electric water heaters

- Hot tubs or spas

- Home workshops with larger tools or compressors

- Whole-home standby generators or battery backup systems

What can catch a homeowner off guard is that it’s not always the newest appliance that causes the issue. It’s the cumulative load. A panel that handled everything fine ten years ago may not have the headroom left after a few incremental upgrades.

Subpanels

A subpanel is a secondary electrical panel that’s fed from the main panel. It doesn’t receive power directly from the utility. Instead, it distributes power that already passes through the main service equipment. Subpanels are commonly used to organize circuits for a specific area, such as a garage, workshop, addition, or detached structure.

What a subpanel does well is solve space and layout problems. When the main panel is physically full but still has adequate capacity, a subpanel can provide additional breaker space closer to where the circuits are needed. This can reduce long wire runs, improve organization, and make future changes easier within that specific area of the home.

What a subpanel does not do is increase the home’s electrical capacity. The total load is still limited by the main panel and service amperage. Every circuit in a subpanel counts toward the same overall load calculation as circuits in the main panel. If the main panel is already operating near its limits, adding a subpanel simply redistributes circuits without addressing the underlying constraint.

This distinction is where confusion often comes in. A subpanel is sometimes suggested as a quick fix when a panel is full, but if the service capacity is already tight, that fix only delays the real solution. In those cases, a panel upgrade is the appropriate step because it increases available amperage and restores margin across the entire system.

Subpanels make sense when the main panel has sufficient capacity and the issue is organization or distance. Panel upgrades make sense when the home’s electrical demand has outgrown what the existing service can safely support. Understanding which problem is being solved prevents unnecessary work and ensures the system is built around actual electrical needs rather than short-term convenience.

Code Compliance & Safety Considerations

Electrical codes evolve to reflect real-world failure data. Panels installed decades ago may still function, but they often lack modern safety features such as improved grounding methods, arc-fault protection, or proper labeling and disconnect requirements. Insurance carriers and home inspectors increasingly flag outdated panels during inspections, especially when known problem models are present. Replacement eliminates those risks and brings the system into alignment with current safety standards.

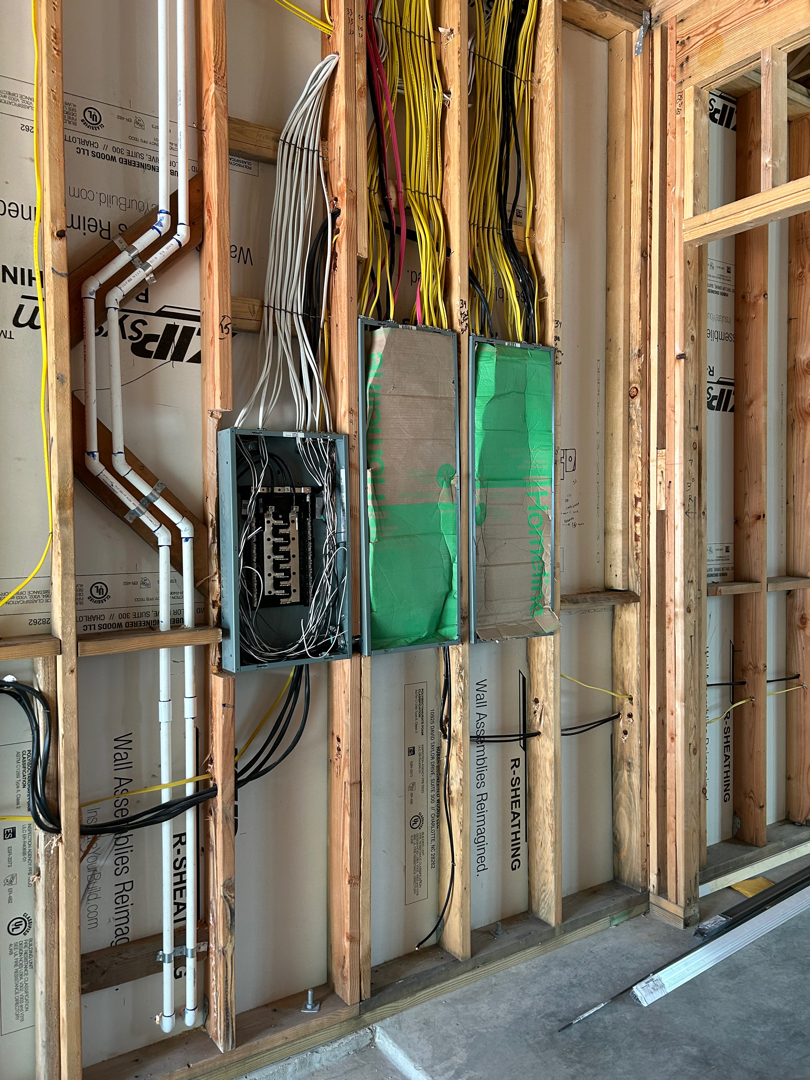

What Happens During a Panel Upgrade or Replacement

From the outside, panel work can sound disruptive or complicated. In reality, it’s a controlled, step-by-step process, and the electrician handles the coordination so the work moves cleanly from start to finish.

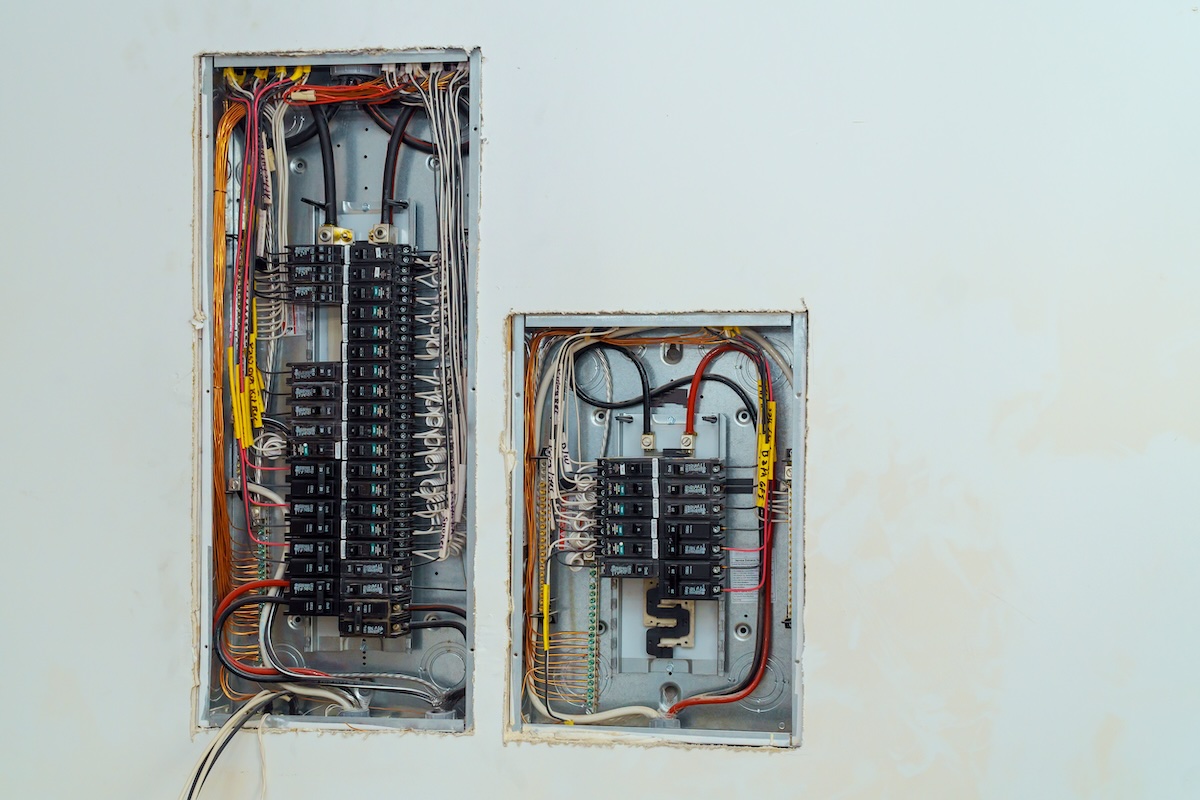

The job begins with shutting down power at the utility connection. Once the system is de-energized, the existing panel is removed and the new enclosure is installed in its place. Circuits are transferred one at a time, labeled properly, and landed on new breakers sized for the wiring they serve. Grounding and bonding are brought up to current standards, which is a critical part of modern panel work and often an area where older installations fall short.

If the project includes a service upgrade, coordination with the utility provider may need to be part of the scope. For example, scheduling disconnects and reconnects, confirming service requirements, and making sure the meter and service conductors meet current specifications. Permits and inspections may need to be pulled and managed so the work complies with local electrical code and utility rules before the system is energized again.

By the time power is restored, the panel has been rebuilt as a coherent system rather than a patchwork of old and new components. The intent is a clean handoff back to normal operation, with the panel properly sized, clearly organized, and ready to support the home without workarounds or lingering questions.

When to Evaluate Your Electrical Panel

There are certain points where it makes sense to pause and take a hard look at the panel, even if nothing has failed outright. Major appliance changes are one of them. Adding equipment with higher electrical demand, replacing gas appliances with electric, or planning for future loads changes how the system is used, and the panel needs to be evaluated in that context rather than assumed to be adequate.

Home renovations are another natural checkpoint. When walls are open or circuits are being modified, it’s the right time to assess whether the panel can support the updated layout without relying on shared circuits or temporary fixes. Repeated breaker trips, flickering under load, or a panel that’s completely full are also signals that the system may be operating too close to its limits.

Older homes deserve special attention. Panels installed decades ago were built to different standards and expectations. During a home purchase or inspection, confirming that the panel matches current electrical demands and safety requirements can prevent surprises later, especially when updates or additions are planned.

Addressing panel limitations early prevents cascading electrical problems later. The panel sets the ceiling for what the rest of the system can safely support. Making sure that ceiling is appropriate allows the rest of the system to function as intended, without forcing compromises elsewhere.

Electrical Panel & Power System Glossary

This glossary is intended to clarify terms that commonly come up during discussions about panel upgrades, replacements, and backup power planning, so homeowners can better understand how their electrical system is structured and why certain recommendations are made.

Electrical Panel

The central enclosure that receives power from the utility service and distributes it to individual circuits throughout the home. It contains breakers, grounding connections, and the main service disconnect.

Panel Upgrade

Work performed to increase the electrical capacity of a home, usually by raising the service amperage and installing a larger panel with more breaker space.

Panel Replacement

Removal and installation of a new electrical panel due to age, condition, safety concerns, or obsolete design, without necessarily increasing service amperage.

Service Amperage (Service Size)

The maximum amount of electrical current the home is designed to handle at one time, commonly 100, 150, or 200 amps in residential settings.

Breaker (Circuit Breaker)

A safety device that automatically shuts off power to a circuit when current exceeds safe limits, protecting wiring and connected equipment.

Branch Circuit

A circuit that runs from the electrical panel to outlets, lighting, or appliances, protected by an individual breaker.

Main Breaker

The primary disconnect in the panel that shuts off power to all branch circuits at once.

Bus Bar

Metal bars inside the panel that distribute power to individual breakers. Wear or damage here can affect multiple circuits.

Overcurrent Protection

Safety mechanisms, such as breakers, that interrupt electrical flow when current becomes excessive.

Voltage Drop

A reduction in voltage caused by electrical resistance under load, often noticeable as dimming lights or sluggish appliance performance.

Load

The amount of electrical power being drawn by appliances, lighting, and equipment at a given time.

Load Calculation

A standardized method used to determine whether a panel and service can safely support existing and planned electrical loads.

Continuous Load

An electrical load expected to run for three hours or more, such as EV chargers or certain HVAC equipment, requiring special consideration in panel sizing.

Grounding

A system that provides a direct path for fault current to the earth, reducing shock and fire risk.

Bonding

The process of connecting metal components together to ensure electrical continuity and safe fault current flow.

Service Upgrade

An increase in the electrical service capacity from the utility to the home, often performed alongside a panel upgrade.

Manual Transfer Switch

A device that allows selected circuits to be powered by a generator during an outage through manual operation.

Automatic Transfer Switch (ATS)

A system that automatically switches the home from utility power to generator power when an outage occurs.

Interlock Kit

A mechanical device installed on certain panels that prevents the main breaker and a generator backfeed breaker from being on at the same time.

Backfeed

The method of supplying generator power to a panel through a breaker, requiring approved equipment and safeguards.

Utility Service

The power supply provided by the electric utility company to the home.

Service Disconnect

A means of shutting off all power to the home, typically located at the panel or meter.

Arc-Fault Protection (AFCI)

A type of breaker designed to detect dangerous electrical arcing and shut off power to prevent fires.

Panel Rating

The maximum amperage the panel is designed to handle safely.

Breaker Space

Available slots in a panel for adding new circuits.

The Takeaway

If you’ve made it this far, the takeaway is pretty simple. When a panel is outdated, undersized, or pushed beyond what it was built to handle, the rest of the electrical system ends up compensating. Sometimes that shows up as nuisance issues. Other times it shows up when you try to add something new and realize the panel is the limiting factor.

A panel evaluation doesn’t have to mean a full replacement. Sometimes it’s confirming the panel is still appropriate. Sometimes it’s planning ahead for a new appliance, a generator connection, or future electrical loads. It’s important to know what the system can safely support and what it can’t.

As a licensed and insured electrical contractor, we’re your dedicated partner in providing residential and commercial solutions with precision, professionalism, and a personal touch. Contact BrotherlyLove Electric at:

Houston: (346) 777-3370

Dallas: (214) 303-9055